Is Your iPhone Spying on You?

Learn to navigate the mysterious world of smartphone privacy.

Many of us have had a conversation with a friend, only to be scrolling on our phones later and come across an ad for the very thing we thought we’d been discussing in private. My colleague, Erin MacPherson, told me this story: “My mom was talking to me about wanting a side-by-side double trash can for under her breakfast bar, and a few days later, I was seeing Amazon ads for exactly those. It was... freaky. Up until then, I had pretty much assumed that I’d forgotten about Googling something or looking it up on Amazon, but I was sure I hadn’t with that one.” Stories like this raise the question—is your iPhone spying on you?

Related: How to Know If Someone Blocked Your Number on iPhone

In 2021, the debate over iPhone privacy has been blowing up on a major scale. Apple’s new initiative to scan material on users’ phones for potential child sexual abuse material (CSAM) was delayed after pushback from individuals and organizations concerned about the new policy’s privacy and security implications. Edward Snowden, among others, spoke out on Twitter and published an article about Apple’s plans to start scanning images intended for upload to iCloud and information exchanged using the Messages app for CSAM in collaboration with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC).

While this might sound like a noble pursuit—I think we can all agree that reducing the proliferation of CSAM online is of paramount importance—Snowden and others were concerned that, with this initiative, Apple would open a “back door” to abuses of privacy. If Apple were to scan and share your photos and encrypted messages, who’s to say where this sharing would stop? What other types of images and messages might Apple decide are dangerous? Who else might the company be compelled to share your data with?

As Snowden writes, “...it really doesn’t matter what Apple’s claimed process protections are: once they create the capability, the law will change to direct its application. . . The bottom line is that once Apple crafts a mechanism [for] the mass surveillance of iPhones (no matter how carefully implemented), they lose the ability to determine what purposes it is used for.”

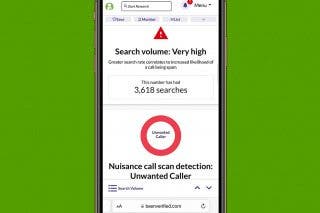

The battle over privacy concerns regarding Apple’s child safety protections comes in contrast to its efforts to stand out as the tech company most dedicated to preserving users’ privacy. With the rollout of App Tracking Transparency in iOS 14.5, Apple threw the gauntlet at Meta’s (formerly Facebook) feet, forcing the notorious data miner to announce its intention to track users and give them the option to opt out of tracking. The results weren’t pretty for Meta and other app developers: 96 percent of iPhone users in the US refused to surrender their data. Since then, Apple has only continued to build its privacy protections with iOS 15, introducing iCloud Private Relay to help users browse more securely and expanding its Hide My Email feature to protect users’ email addresses from spam and scammers.

So, which is it? Is Apple truly dedicated to protecting your privacy, or is it opening you up to data mining and intrusive governmental overreach?

The answer to that question is: It’s complicated. While Apple’s plans to start doing client-side scanning to search for CSAM on users’ iPhones have been delayed, the initiative has not been canceled. According to a statement Apple made to Gizmodo: “Based on feedback from customers, advocacy groups, researchers and others, we have decided to take additional time over the coming months to collect input and make improvements before releasing these critically important child safety features.”

If your iPhone can soon scan your iCloud-bound images and messages, what can it do now?

You should know that both native Apple apps (like the Camera app or Apple Maps) and third-party apps frequently collect data such as your location and can access your microphone and camera, depending on the permissions you set. Third-party apps may also use third-party trackers to collect data about users. Many apps will even collect information like your name, age, location, interactions on the app, and even your outside internet activity.

Apple’s App Tracking Transparency feature makes it easier to limit the data third-party apps can collect on you, but depending on the terms you agreed to when you signed up for the app, it may not stop apps from collecting all of it. Keep in mind that many apps require permission to use your camera, microphone, and location to function. What good would navigating with Google Maps be if it didn’t know where you were? Wouldn’t it be a lot harder to post a story to Instagram if the app didn’t have access to your camera? Well, according to a lawsuit filed in September 2020, Instagram (which is owned by Facebook parent company Meta) was sued for allegedly accessing users’ cameras even when the users were not actively using Instagram.

This lawsuit, filed by Brittany Conditi on behalf of herself and other Instagram users, alleges that Instagram accesses users’ cameras even when the Instagram camera feature is not in use “for one main reason: to collect lucrative and valuable data on its users that it would not otherwise have access to.” The suit goes on to say, “By obtaining extremely private and intimate personal data on their users, including in the privacy of their own homes, [Meta is] able to increase their advertising revenue by targeting users more than ever before.”

According to The Fashion Law, a media company following (you guessed it) legal aspects of the fashion industry, Conditi dropped her lawsuit in 2021, which The Fashion Law claims is “likely the result of a confidential settlement between the parties.” This means that we may never know what Meta admitted to in the settlement and what they denied, but earlier in 2020, Meta did address an Instagram “bug” that gave the app access to users’ cameras even when they were not using the app.

Interestingly, Conditi’s suit specifically credits Apple’s iOS 14—which sends notifications to users when a third-party app accesses their cameras or microphones—with exposing Instagram’s alleged improper use of users’ cameras. That’s a point in Apple’s favor, and so is Security.org’s rating of A+ for Apple’s data collection policies. According to Aliza Vigderman, tech journalist and Security. org’s Content Manager, your data is much safer with an iPhone than with an Android phone. “Google collects much more information than Apple,” she says.

But what about my colleague Erin’s story of suddenly receiving ads for a product she’d only spoken privately with her mother about? The ads Erin saw appeared on Facebook. How could Amazon and Meta have known that Erin talked to her mother about fancy new side-by-side trash cans unless her phone told them?

Well, there is a (somewhat) innocent explanation. According to Rex Freiberger, CEO of the tech publication Gadget Review, “This is the result of advanced algorithms that definitely do track your online activity but aren’t listening in on you.” You see, Erin is Facebook friends with her mom, and while Erin may not have searched online for side-by-side trash cans, her mother did. As we’ve gone over, apps like Facebook can pinpoint your location, so they might be able to see that Erin and her mother are friends who are frequently in the same place—maybe the same house. So, if Meta knew to serve Erin’s mother ads about side-by-side trash cans based on her search history, it might have known to serve Erin those ads as well, as she also spent a lot of time in a household that was in the market for said trash cans.

Freiberger goes on to say that noticing ads for things we were just talking about is also likely “a result of confirmation bias.” How many conversations do we have daily, and how many ads do we see? Every time there’s an overlap, we might jump to the conclusion that it’s the result of our iPhones recording our conversations, especially if we’re already concerned about our phones spying on us.

If this explanation doesn’t satisfy you, you’re not alone. It doesn’t help that, of course, companies like Meta don’t want anyone to know the breadth of the data they collect and how they’re doing it. For its part, Meta has been very clear that it does not use your phone’s microphone to listen in on your conversations. Apple also denies using iPhone microphones or cameras to spy on users, but this is cold comfort for those who worry about their privacy when they have an iPhone in the room with them.

The good news is, you’re not totally helpless when it comes to protecting your data. If you want to minimize the amount your iPhone apps can track you: Turn off tracking for apps using the App Tracking Transparency feature and turn off Location Services either for your entire iPhone or on an app-by-app basis. Mask your email address with the Hide My Email feature when you sign up for apps. Check to see which apps have permission to use your microphone and camera and disallow those you don’t trust. Most importantly, do your research on the apps that you install on your iPhone.

Most of the more mysterious and intrusive data mining comes from third-party apps, not Apple apps. Before installing a new app from the App Store, make sure to look the developer up, read reviews, check the permissions it requires, and read the terms of service (yes, I know). Vigderman stresses the importance of managing which apps you allow to track you: “Whenever you are asked if an app can track you, decline it."

You should also remember: If you’re not paying for a product, you are the product. Nowhere is this truer than in the world of apps.

Top image credit: FullRix/Shutterstock.com

August Garry

August Garry is an Associate Editor for iPhone Life. Formerly of Gartner and Software Advice, they have six years of experience writing about technology for everyday users, specializing in iPhones, HomePods, and Apple TV. As a former college writing instructor, they are passionate about effective, accessible communication, which is perhaps why they love helping readers master the strongest communication tools they have available: their iPhones. They have a degree in Russian Literature and Language from Reed College.

When they’re not writing for iPhone Life, they’re reading about maritime disasters, writing fiction, rock climbing, or walking their adorable dog, Moosh.

Olena Kagui

Olena Kagui

Susan Misuraca

Susan Misuraca

Rachel Needell

Rachel Needell

Leanne Hays

Leanne Hays

Rhett Intriago

Rhett Intriago

Amy Spitzfaden Both

Amy Spitzfaden Both

August Garry

August Garry

Cullen Thomas

Cullen Thomas