Color me a virtual-reality optimist. Alongside writing for iPhone Life, I’m a video game developer, 3D artist, and sci-fi author. I own a Meta Quest 3 and use it all the time to play games and view 3D models as I work. My first experience of VR on a Valve Index is a cherished memory—it was so much fun to explore video game environments as if actually visiting them! When Apple announced its premium augmented reality headset, the Vision Pro, I was about as excited as anybody could be. That is, until I tried it.

Some Quick Definitions for the Uninitiated

Virtual reality (VR) refers to immersive worlds portrayed using headsets that have one screen for each of your eyes, so you can see in 3D. When you put on a VR headset, the world around you disappears and you’re plunged into an environment that’s created using video game technology.

“I was sitting at my dining room table, wearing the Vision Pro, looking back and forth between floating app windows and the real windows out onto my yard, and for a moment I thought, ‘This is cool.’”

Augmented Reality (AR) is an improvement on VR technology that uses cameras on the outside of the device to capture your actual environment and show it to you on the screens displaying the virtual content, an effect called passthrough. This is super helpful for things like finding your drink on the counter and not bumping into chairs, but it also paves the way for experiences that blend the real with the virtual. Apple has bet big on that idea with the Vision Pro. For all the latest news on the Vision Pro, be sure to check out our free Tip of the Day newsletter.

Vision Pro vs Meta Quest 3

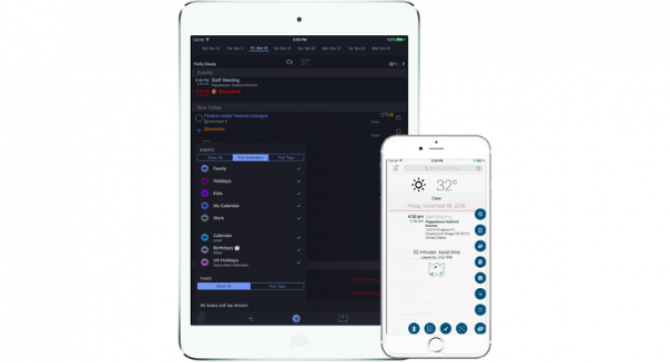

The Vision Pro is essentially a Mac packed into thick ski goggles, equipped with advanced camera systems, hand tracking, eye tracking, face tracking, and dazzling high-resolution screens for each eye. It promises what Apple calls spatial computing, that is, the experience of computer content that is not trapped inside a monitor, but instead experienced in the space around you.

“The hand and eye tracking work like magic: you can interact with your apps like Tom Cruise in Minority Report, or Robert Downey Jr. as Tony Stark tinkering with his Iron Man suit in hologram form.”

It isn’t the first headset to offer this. The most popular is the Quest 3 made by Meta. Either of these headsets project your app windows into the world around you as floating panes of glass hovering anywhere you put them—over your desk, over your kitchen table, above you, behind you, inside your pantry—you name it. You have essentially infinite monitor real estate, because there is no monitor. The headsets can also erase the world around you to immerse you in beautiful environments, from national parks and monuments to the surface of the moon on the Vision Pro, or any world that video games can create on the Quest 3. In the future, AR headsets will be able to enhance your surroundings with digital overlays and graphics. For example, imagine repairing your car wearing goggles that scan the engine, identify the parts, and show step-by-step instructions floating next to each problem.

Taken together, these experiences promise a high-tech future, but one of these two devices is way better than the other, and it’s for reasons I didn’t expect.

By every technical measure, the Vision Pro beats the socks off the Meta Quest 3. It’s got way better screens. Its motion tracking and hand tracking feel superior. It has features the Quest 3 lacks: eye tracking so you can activate interface elements merely by looking at them, face tracking to animate a virtual avatar with the movements of your lips as you talk, smile, or laugh. It’s got a far superior processor, far superior build quality, and far superior battery life. The operating system is a blend of Apple’s familiar and aesthetic designs from MacOS and iOS, compared to a clunky Android-based interface on the Meta Quest 3.

However, the Meta Quest 3 has a (much) lower price tag ($499 compared to $3,600) and—most importantly—controllers you hold in your hands, a familiar interface that lets you play games and navigate virtual environments. The Vision Pro doesn’t have these at all, and without them, you can tap on the holographic windows and navigate touch apps, but you can’t move a virtual avatar around a 3D space, so there are no immersive games to play. The controllers are a surprisingly big deal.

A Vision of the Future

When I first put on a Valve Index and explored a virtual reality, I was blown away by the potential of the technology. Each new generation of VR and AR headsets has brought more features and more realism—better displays, better graphics, more accurate tracking of head position and hand position—fulfilling the sci-fi promise made by the technology. With each new device my excitement has grown.

Then I put on the Vision Pro and saw what the future of the technology holds. It’s the first genuinely acceptable passthrough: you mostly feel like you’re wearing heavy ski goggles, and I could imagine myself wearing the headset around the house, interacting with projected apps. It offers face tracking for a digital avatar: you can see your own face animated in a digital world, and you can easily believe in a Ready Player One style social life playing out using digital avatars. The hand and eye tracking work like magic: you can interact with your apps likeTom Cruise in Minority Report, or Robert Downey Jr. asTony Stark tinkering with his Iron Man suit in hologram form.

The passthrough on the Vision Pro is remarkably clear. I was sitting at my dining room table, wearing the Vision Pro, looking back and forth between floating app windows and the real windows out onto my yard, and for a moment I thought, “This is cool.” The promise of spatial computing seemed momentarily plausible, the apps liberated from their screens, the computer seeming invisibly integrated with the world. Then I tried to work on this article, got frustrated by having to poke intangible buttons, and took the thing off to discover that my eyes hurt and the world looked a lot better outside the headset.

“Why would you want to write with your computer strapped to your face?”

No matter how good the cameras are that capture the world or how good the screens are to show it, you’re still looking at screens two inches from your eyeballs. My big takeaway from trying the amazing screens on the Vision Pro is that staring at screens two inches from your eyeballs is not the same as wearing transparent goggles, and it never will be.

Waving your hands around to interact with apps is exhausting and cumbersome compared to the ease and versatility of a mouse and keyboard. I don’t expect that to ever change.

You can work on your spreadsheets or documents with the Vision Pro (that seems to be what it’s designed to do), but why would you want to write with your computer strapped to your face? It’s not that nice after a while—it gets funky, feels weird, and leaves marks.

Vision Pro may deliver sci-fi ideas, but it also brings crashing home the unfortunate experience that looking cool in a sci-fi movie doesn’t make something a good idea. The future that the Vision Pro represents is awkward, socially disconnected, impractical, and uncomfortable.

Okay, If Not Productivity, Maybe Entertainment?

It’s cool to be able to project Netflix on a virtual screen the size of a sports stadium situated on the moon right up until you want to share a moment with the person sitting next to you. Most of us do our Netflix binge with company, but Vision Pro doesn’t have room for two, and it never will.

VR headsets don’t need to divide. There are tons of fun things to do to connect with others in virtual environments—that’s what multiplayer video games are. Gamers have been connecting in virtual environments for decades, long before headsets like this. People have weddings in World of Warcraft, where they actually get married. VR promises to offer even more compelling versions of that. But the value of these interactions and the strength of these connections are built in shared play. They’re produced by playing together, which means games. The Quest 3 offers virtual play in the form of the Metaverse, which is weird but full of silliness and novelty and every time I log in, I see bemused people everywhere chatting and exploring the technology. The Vision Pro does not come equipped with any silly, novel experiences where people can have fun and connect. It’s early days, so that may change, but Apple has historically struggled to convince game makers to make games for their systems, and the lack of controllers indicates that Apple doesn’t want that to change.

“The Vision Pro is specifically designed to do exactly what it’s worst at: office jobs and watching TV.”

While wearing any VR headset, nobody can see your face, greatly restricting your ability to connect with others. Meta tackled this with the Metaverse. Apple doesn’t offer anything like that so they made a system where the Vision Pro scans your face and creates a digital avatar that looks just like you. The headset then maps your face movements onto the avatar for your interlocutors to see while you’re on regular FaceTIme and Zoom video calls. This worked both better than I expected and much worse. Better in that my avatar did look like me, worse in how it was an early 2000s CGI version of me, somehow transparent in a way that made my coworkers call the ghostbusters. A similar technology would be a fantastic addition to the Metaverse, but it can’t work, and never will work, in business calls where identities have to be verified and authenticity matters. It’s silly, but not in a way that facilitates play, work, or anything else.

So, What Are These Things For?

I see a future for virtual reality. It’s going to continue to appeal to a demographic that craves the infinite field of novel experiences. The entertainment value is limitless, and VR offers shared experiences and culture that could eventually go mainstream in a big way. Meta Quest 3 is designed for delivering novel experiences and stories to share in VR.

I am much less optimistic about augmented reality and spatial computing. The overlay of digital elements over our real-world environment is already useful in the industrial design sector for things like product visualization, engineering, and architecture. But strapping the computer to your face is a terrible way to try to work an office job or watch TV. Ironically, the Vision Pro is specifically designed to do exactly what it’s worst at: office jobs and watching TV.

Apple’s $3,600 headset may be something akin to a prototype, priced out of the hands of everyday consumers and aimed at the developer market, educational institutions, and industrial users. But to me, the main takeaway isn’t just that Apple’s emphasis on augmented reality for everyday productivity doesn’t work, it’s that it never will.